I. INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Observers have estimated that between seventy and one hundred million American citizens possess some form of a criminal record.[1] Because this number is so massive, the issue of the collateral consequences of conviction has become an extremely important area of study. Collateral consequences are defined as “the penalties, disabilities, or disadvantages imposed upon a person as a result of a criminal conviction, either automatically by operation of law or by authorized action of an administrative agency or court on a case by case basis.”[2] The American Bar Association has catalogued approximately 44,500 collateral consequences of criminal conviction,[3] including denials of public housing and public assistance, deportation, disenfranchisement, and licensing or employment restrictions in a variety of occupations.[4] As scholars Jessica Henry and James Jacobs have noted, “[t]he burgeoning proliferation of criminal records and the de jure and de facto discrimination against ex-offenders combine to create the prospect of a permanent underclass of ex-offenders who are excluded from the legitimate economy and are funneled into a cycle of additional criminality and imprisonment.”[5]

One of the most punitive collateral consequences of conviction is the impact of a criminal record on the likelihood of securing employment.[6] Research on the relationship between employment and reentry consistently demonstrates that employment is correlated with lower rates of reoffending and therefore with successful reentry.[7] However, ex-offenders face tremendous challenges in finding adequate employment,[8] including the increased use of criminal background checks in hiring decisions.[9] A survey conducted by the Society for Human Resource Management found that nearly ninety percent of surveyed organizations reported conducting criminal background checks on at least some job candidates, and nearly seventy percent reported conducting criminal background checks on all job candidates.[10] The large number of Americans with criminal histories combined with the high prevalence of employer background checks has the effect of excluding many individuals from legitimate employment. Empirical studies using various designs have consistently found that employers are less likely to hire individuals who have criminal records.[11]

Many jurisdictions have created mechanisms aimed at lessening the collateral consequences of conviction, particularly those related to employment. Such mechanisms include clemency, expungement, and certificates of relief.[12] Between 2009 and 2014, forty-one states and the District of Columbia enacted legislation to ease the harsh effects of a criminal conviction.[13] Several states passed laws expanding or strengthening pardon relief, expungement relief, or both, most commonly by extending the availability of such relief, clarifying its effects, reducing waiting periods, and altering the burden of proof required to obtain it.[14] Although pardons and expungements can be effective tools for mitigating the burden of collateral consequences, the process can be lengthy, expensive, and cumbersome for ex-offenders to navigate.[15]

One new and innovative mechanism for relieving collateral consequences is the certificate of relief (also known as the certificate of recovery or the certificate of qualification for employment), which is meant to avoid the shortcomings of pardons and expungement.[16] Certificates of relief are intended to demonstrate that ex-offenders have been rehabilitated, while stopping short of sealing the applicants’ records. These certificates demonstrate rehabilitation for an ex-offender when he or she satisfies the statutory requirements, such as a waiting period or requirements relating to individual need and community safety.[17] These certificates aid ex-offenders in their employment searches because, depending on the statute, such mechanisms may remove automatic licensing bars for those with criminal records,[18] offer a stamp of good character from a court,[19] or protect employers who hire ex-offenders from negligent hiring claims.[20] Recent research on these certificates demonstrates both the potential benefits of such mechanisms and the difficulty of uniform implementation.[21] However, the previous studies were qualitative in nature and focused on perceptions of the certificates.[22] While these studies can provide valuable insight, they supply limited information regarding causality. When Ohio created its Certificate of Qualification for Employment (CQE) with Ohio Senate Bill 337,[23] effective September 28, 2012, it provided an excellent research opportunity.[24] The objective of the present study is to empirically examine the impact of Ohio’s CQE.

II. METHODOLOGY

To test the effectiveness of Ohio’s CQE, the present study used an experimental design, which is the gold standard for determining causal inference.[25] Using an experimental-correspondence approach, which relies on sending fictitious resumes to employers, we created three sets of resumes with identical names (in this case, Matthew O’Brien),[26] educational backgrounds, employment experiences, and key skills. Because nearly ninety percent of state prisoners have an educational attainment of at most a high school diploma or its equivalent,[27] each applicant listed a high school diploma as his highest level of educational attainment. Given the dearth of evidence on the work histories of inmates prior to incarceration, we chose to assign favorable and consistent work histories to the fictitious applicants.[28] Each resume included past employment in manufacturing, sales or customer service, and entry-level restaurant work.

The only difference between the applications was whether an affirmative statement regarding a criminal record accompanied the resume, and if so, what type of criminal record the affirmative statement indicated. Like Pager and colleagues,[29] we chose to focus on the impact of a drug-related criminal record on employment opportunities. Sets of resumes were created with, and assigned to, three possible self-disclosed criminal histories: (1) a one-year-old felony drug conviction, (2) a one-year-old felony drug conviction with a certificate of qualification for employment, and (3) as the control group, no self-disclosure of a criminal record. The resumes containing these experimental treatments were then randomly assigned to a random sample of potential employers.

Fieldwork for this study took place in Columbus, Ohio. Columbus was selected because of Ohio’s recent enactment of the CQE program and because of the first author’s familiarity with reentry challenges in the Columbus metropolitan area.[30] During the period of data collection (May to August 2015), economic conditions in Columbus, Ohio, were moderately strong as unemployment rates held steady at approximately one percentage point lower than the U.S. national average,[31] ranging from a high of 4.3% in June and July to a low of 3.8% in August.[32] In 2014, Ohio had a correctional population of more than fifty thousand people,[33] and over twenty thousand individuals were released from correctional facilities in that year alone.[34]

Data collection took place over ten weeks between May and August of 2015. Every week during that period, the first author created a population list of all entry-level[35] employment ads from the websites CareerBuilder.com, Craigslist.com, and Indeed.com[36] that were listed within the geographical area of Columbus, Ohio, and were posted within the preceding two weeks.[37] From that weekly population list, the first author randomly drew thirty-two employers for random assignment to one of the resume types. A total of 320 resumes were submitted to 320 employment postings over the data-collection period. One employer contacted the fictional applicant to report the job had already been filled. That application was excluded from the analysis,[38] which resulted in a final sample size of 319 job applications. To measure employer response, the first author monitored an email account that was registered to Matthew O’Brien[39] and a voicemail that used the default, anonymous greeting. Responses were recorded as positive when fictional applicants received an interview invitation or an offer of employment.[40]

III. RESULTS

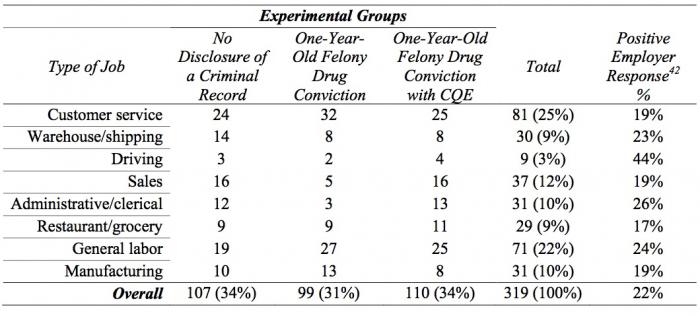

The sample of jobs in this study is presented in Table 1. For descriptive purposes, we created eight categories of the entry-level jobs. The categories were administrative/clerical, customer service, restaurant/grocery, sales, driving, warehouse/shipping, manufacturing, and general labor. The categories are comparable to those in previous studies,[41] and the distribution of jobs in the sample matches the general distribution of sought positions at the Ohio reentry facility observed by the first author. Table 1 also presents the percentage of resume applications within each job type that received a positive response. Overall, nearly one quarter of applications received an interview invitation or offer of employment. Employer responses differed across occupational categories, with applications for driving jobs eliciting the highest callback rate (44%), while applications for restaurant or grocery occupations had the lowest callback rate (17%).

Table 1: Frequency of Resumes Submitted, by Treatment Group and Occupational Category (N = 319)

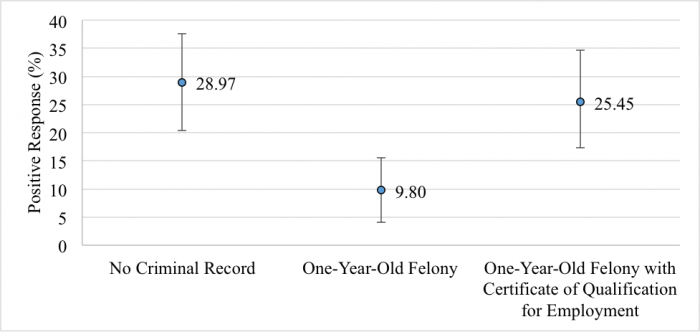

Figure 1 compares positive outcomes of employment decisions (interview invitations or job offers) of equally qualified fictional applicants with no disclosed criminal record, a one-year-old felony drug conviction, and a one-year-old felony drug conviction with a CQE. It is useful to first compare applicants with a clean background to those with a one-year-old felony drug conviction and no certificate. As illustrated in Figure 1, a criminal record has a large and significant effect on employment opportunities, with nearly thirty percent of applicants without criminal records receiving interview invitations or offers of employment, compared to fewer than ten percent of applicants who disclosed recent felony drug convictions without a CQE. Thus, the proportion of applicants with criminal records who received interview invitations or job offers was more than sixty-six percent lower than the proportion of their equally qualified counterparts with clean records. These results demonstrate that a criminal record greatly limits employment opportunities during this crucial initial stage of the employment process.

Figure 1:[43] The Effect of Certificates of Qualification for Employment on Positive Employer Responses[44] (N = 319)[45]

Our primary research question involves the ability of Ohio’s CQEs to alleviate the employment-related collateral consequences of conviction illustrated above. As Figure 1 indicates, CQEs appear to offer a great benefit to job seekers with criminal records. Although a slightly higher proportion of applicants with clean backgrounds received interview invitations or job offers than did those with one-year-old felonies and CQEs, this difference does not reach statistical significance. In other words, there is no evidence to suggest that individuals with CQEs fare any worse on the job market than do those with clean backgrounds. Further, for individuals with a one-year-old felony drug conviction, this study suggests that obtaining a CQE may increase the likelihood of receiving an interview invitation or job offer threefold. Taken together, these promising results suggest that the stigma of a recent felony drug conviction as it relates to hiring decisions may be alleviated for those who receive CQEs, and that employers in Ohio’s entry-level job market are open to considering hiring certificate holders.

IV. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The present study offers an important first step toward understanding the efficacy of one possible employment-related collateral consequence relief mechanism. Our findings indicate that these certificates have tangible benefits to employment seekers possessing criminal records. When applying for jobs that did not explicitly bar applicants with criminal records, ex-offenders holding certificates received nearly three times as many interview invitations or job offers as did those with equivalent criminal records and qualifications and no CQE. Such a finding should be encouraging for jurisdictions that have enacted similar statutes as well as for those seeking to create an intermediate relief mechanism, like a CQE, that stops short of completely sealing a criminal record.

Although our initial findings are promising, future research is needed to expand our understanding of the efficacy of certificates of relief. First, while there is much similarity between Ohio’s CQE and other versions of such certificates,[46] which is encouraging for other jurisdictions given the results of the present study, it is inappropriate to assume similar results in those other jurisdictions without further study.[47] Further research is needed to determine whether specific elements of the Ohio CQE statute drove the present results. For example, it is unclear to what extent the protections for employers against negligent hiring claims or the implied character-affirming nature of the certificate contributed to the present study’s results.[48]

Second, there is a considerable body of research documenting that minority job seekers with criminal records face an added disadvantage compared to white job seekers possessing a criminal record.[49] This means that the certificates discussed here may not be as effective for minority ex-offenders. Third, research in the private housing context demonstrates that ex-offenders possessing felony convictions for sex offenses fare worse in securing private housing than do ex-offenders possessing drug convictions.[50] This could mean that certificates of relief may not be as effective for those possessing convictions for certain categories of violent offenses. Therefore, future research should also include race and different types of offenses to further test the effectiveness of certificates of relief.[51]

Finally, research is needed to determine the practical availability of such mechanisms. For instance, do eligible ex-offenders know that such mechanisms exist in their jurisdictions? Are ex-offenders able to navigate the legal process in order to be granted certificates? Can ex-offenders afford the fees associated with such a legal process? These questions must be answered before such mechanisms can truly be seen as practical tools to reduce employment discrimination and increase the civil rights of ex-offenders. In the end, such tools are only likely to reduce discrimination based upon criminal records, not to eliminate it entirely. Perhaps the only way to eliminate such discrimination would be to implement “ban-the-box” policies and prohibit employment decisions based on criminal records unless related to the job position.[52]

In summary, various studies have recognized the important link between employment and successful reentry. However, research also shows the harsh effects of criminal-record stigma on employment outcomes, making successful reentry extremely difficult. The present study suggests that certificates of relief may be an effective avenue for reducing the stigma of a criminal record for ex-offenders seeking employment. While the results are encouraging, future research is needed in order to determine the full utility of these certificates.

[1] E.g., Rebecca Vallas & Sharon Dietrich, One Strike and You’re Out: How We Can Eliminate Barriers to Economic Security and Mobility for People with Criminal Records, Ctr. for Am. Progress (Dec. 2, 2014, 7:35 AM), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/report/2014/12/….

[2] User Guide Frequently Asked Questions, Am. B. Ass’n Nat’l Inventory Collateral Consequences Conviction (2013), http://www.abacollateralconsequences.org/user_guide/#q01.

[3] The National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction (NICCC), Am. B. Ass’n, www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/events/criminal_justice/annual14_Bar… (last visited Oct. 27, 2016).

[4] See National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction, Am. B. Ass’n Nat’l Inventory Collateral Consequences Conviction (2013), http://www.abacollateralconsequences.org/map/.

[5] Jessica S. Henry & James B. Jacobs, Ban the Box To Promote Ex-Offender Employment, 6 Criminology & Pub. Pol’y 755, 756 (2007) (citations omitted) (citing Margaret Colgate Love, Relief from the Collateral Consequences of a Criminal Conviction: A State-by-State Resource Guide (2006), http://blogs.law.columbia.edu/4cs/files/2008/11/statebystaterelieffromcc… Jessica S. Henry, Closing the Legal Services Gap in Reentry, 21 Crim. Just. Stud.: Critical J. Crime L. & Soc’y 15 (2008); James B. Jacobs, Mass Incarceration and the Proliferation of Criminal Records, 3 U. St. Thomas L.J. 387 (2006)).

[6] See, e.g., Harry J. Holzer, Steven Raphael & Michael A. Stoll, Employment Barriers Facing Ex-Offenders 8-13 (Urban Inst. Reentry Roundtable, Discussion Paper, 2003), http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/41085….

[7] For reviews of such evidence, see Devah Pager, Evidence-Based Policy for Successful Prisoner Reentry, 5 Criminology & Pub. Pol’y 505 (2006) and Christopher Uggen, Work as a Turning Point in the Life Course of Criminals: A Duration Model of Age, Employment, and Recidivism, 67 Am. Soc. Rev. 529 (2000).

[8] See Pager, supra note 7, at 505 (noting the barriers created by incarceration and criminal record stigma in seeking employment).

[9] Michael A. Stoll & Shawn D. Bushway, The Effect of Criminal Background Checks on Hiring Ex-Offenders, 7 Criminology & Pub. Pol’y 371, 396 (2008).

[10] Background Checking: The Use of Criminal Background Checks in Hiring Decisions, Soc’y for Hum. Resource Mgmt. 2 (July 19, 2012), https://www.shrm.org/Hr-Today/Trends-And-Forecasting/Research-And-Survey….

[11] See, e.g., Devah Pager, The Mark of a Criminal Record, 108 Am. J. Soc. 937 (2003) [hereinafter Pager, The Mark of a Criminal Record] (describing perhaps the most notable audit study demonstrating the effect of criminal record stigma on employment outcomes for black and white men); Richard D. Schwartz & Jerome H. Skolnick, Two Studies of Legal Stigma, 10 Soc. Probs. 133, 134-38 (1962) (describing an early correspondence design showing the negative effects of a criminal record on employment outcomes); Christopher Uggen et al., The Edge of Stigma: An Experimental Audit of the Effects of Low-Level Criminal Records on Employment, 52 Criminology 627 (2014) (demonstrating that even an arrest that does not lead to a conviction results in poorer employment outcomes when reported to potential employers). The findings from Pager’s 2003 study were replicated in Scott H. Decker et al., Criminal Stigma, Race, and Ethnicity: The Consequences of Imprisonment for Employment, 43 J. Crim. Just. 108 (2015); and Devah Pager, Bruce Western & Bart Bonikowski, Discrimination in a Low-Wage Labor Market: A Field Experiment, 74 Am. Soc. Rev. 777 (2009) [hereinafter Pager et al., Field Experiment]. Interestingly, however, such studies have largely focused specifically on male ex-offenders. The few studies that have examined this question for female ex-offenders have found little or no impact of a criminal record on employment outcomes. E.g., Sarah Wittig Galgano, Barriers to Reintegration: An Audit Study of the Impact of Race and Offender Status on Employment Opportunities for Women, 30 Soc. Thought & Res. 21, 32-33 (2009); Natalie Rose Ortiz, The Gendering of Criminal Stigma: An Experiment Testing the Effects of Race/Ethnicity and Incarceration on Women’s Entry-Level Job Prospects 129-32 (May 2014) (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Arizona State University), https://repository.asu.edu/attachments/134904/content/Ortiz_asu_0010E_13….

[12] For a state-by-state review of some collateral consequence relief mechanisms, see Margaret Colgate Love, Chart #4: Judicial Expungement, Sealing, and Set-Aside, Collateral Consequences Resource Ctr. (June 2016), http://ccresourcecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Chart-4-Judicial-….

[13] Ram Subramanian, Rebecka Moreno & Sophia Gebreselassie, Vera Inst. of Justice, Relief in Sight?: States Rethink the Collateral Consequences of Criminal Conviction, 2009-2014, at 11 (2014), http://archive.vera.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/states-r….

[14] Id. at 13-18.

[15] See Margaret Colgate Love, Paying Their Debt to Society: Forgiveness, Redemption, and the Uniform Collateral Consequences of Conviction Act, 54 How. L.J. 753, 775-78 (2011).

[16] For examples of certificates of rehabilitation, see Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§ 13-904 to -908 (2016); Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 480(b) (West 2016); 730 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 5 / 5-5.5-25 (West 2016); N.J. Stat. Ann. § 2A:168A-7 (West 2011); and N.Y. Correct. Law §§ 700-706 (McKinney 2016). For an example of a certificate of qualification for employment, see Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2953.25 (West 2016).

[17] See, e.g., Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2953.25(C)(3) (“[A] court that receives an individual’s petition for a certificate of qualification for employment … may issue a certificate of qualification for employment, at the court’s discretion, if the court finds that the individual has established all of the following by a preponderance of the evidence: (a) Granting the petition will materially assist the individual in obtaining employment or occupational licensing. (b) The individual has a substantial need for the relief requested in order to live a law-abiding life. (c) Granting the petition would not pose an unreasonable risk to the safety of the public or any individual.”).

[18] See Margaret Love & April Frazier, Certificates of Rehabilitation and Other Forms of Relief from the Collateral Consequences of Conviction: A Survey of State Laws, in Second Chances in the Criminal Justice System: Alternatives to Incarceration and Reentry Strategies 50, 52-53 (Am. Bar Ass’n Comm’n on Effective Criminal Sanctions ed., 2006).

[19] See id. at 50-51.

[20] See, e.g., Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2953.25(G)(2).

[21] See Alec C. Ewald, Rights Restoration and the Entanglement of US Criminal and Civil Law: A Study of New York’s “Certificates of Relief,” 41 L. & Soc. Inquiry 5 (2016); Heather J. Garretson, Legislating Forgiveness: A Study of Post-Conviction Certificates as Policy To Address the Employment Consequences of a Conviction, 25 B.U. Pub. Int. L.J. 1 (2016).

[22] See Ewald, supra note 21; Garretson, supra note 21.

[23] 2012 Ohio Legis. Serv. Ann. 131 (West) (codified at Ohio Rev. Code. Ann. § 2953.25).

[24] For a discussion of the specifics of the statute as well as its legislative history, see Enactment News: Enacted Senate Bill 337/Collateral Sanctions, Ohio Jud. Conf. (Sept. 28, 2012), http://ohiojudges.org/Document.ashx?DocGuid=58e27087-61e1-4c84-80c3-cde9….

[25] See William R. Shadish, Thomas D. Cook & Donald T. Campbell, Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference (2002), for a detailed discussion on the benefits of using an experimental design.

[26] We chose to focus on male ex-offenders because the U.S. correctional population is predominately male. For example, as of December 31, 2014, there were 5,563,100 men in the total correctional population of the United States but only 1,251,600 women. Danielle Kaeble, Lauren Glaze, Anastasios Tsoutis & Todd Minton, U.S. Dep’t of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, Correctional Populations in the United States, 2014, at 19 (2016), http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus14.pdf.

[27] See Caroline Wolf Harlow, U.S. Dep’t of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, Education and Correctional Populations 1 (2003), http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ecp.pdf.

[28] For a similar approach, see Pager, The Mark of a Criminal Record, supra note 11, at 949-50.

[29] See id. at 949; Pager et al., Field Experiment, supra note 11, at 782.

[30] The first author spent three years conducting observational research at the Columbus Adult Parole Authority and a local reentry facility.

[31] See Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject: Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, U.S. Dep’t Lab. Bureau Lab. Stat., http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000 (last visited Oct. 27, 2016) (demonstrating that the national average unemployment rate in the United States was 5.5% in May 2015, 5.3% in June and July 2015, and 5.1% in August 2015).

[32] Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject: Local Area Unemployment Statistics, U.S. Dep’t Lab. Bureau Lab. Stat., http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LAUMT391814000000003?data_tool=XGtable (last visited Oct. 27, 2016). The unemployment rate in Columbus was 4.1% in May 2015. Id.

[33] E. Ann Carson, U.S. Dep’t of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2014, at 3 (2015), http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p14.pdf.

[34] Id. at 10.

[35] While the statutory language effectuating Ohio’s CQE program primarily discusses lifting automatic licensing bans, see 2012 Ohio Legis. Serv. Ann. 131 (West) (codified at Ohio Rev. Code. Ann. § 2953.25 (West 2016)), other Ohio agencies have stated that the CQE can be used for “general employment opportunities as well,” Certificate of Qualification for Employment (CQE), Ohio Dep’t Rehabilitation & Correction, http://www.drc.ohio.gov/cqe (last visited Oct. 27, 2016), and most CQEs granted in Ohio are used for general employment purposes, John R. Kasich & Gary C. Mohr, Ohio Dep’t of Rehab. & Corr., Certificate of Qualification for Employment (CQE): 2015 Annual Review 5 (2016), http://www.drc.ohio.gov/Portals/0/CQE/CQE_annualreview2015.pdf. The general employment purpose of the CQE is tested here.

[36] There has been a large growth in the number of employers who use the internet to advertise job openings as well as a growth in the number of jobseekers who use the internet to search and apply for jobs. See Alice O. Nakamura et al., Jobs Online, in Studies of Labor Market Intermediation 27, 28 (David H. Autor ed., 2009); Betsey Stevenson, The Internet and Job Search (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research, Working Paper No. 13886, 2008), http://www.nber.org/papers/w13886.pdf.

[37] Thirteen postings were eliminated from the population because they explicitly prohibited applicants with criminal records or required applicants to apply in person. See Pager, The Mark of a Criminal Record, supra note 11, at 968-69, for a similar approach.

[38] However, see infra note 45for an analysis that includes the excluded case.

[39] The address for the email account was matthew_obrien1@outlook.com.

[40] In a similar study, Pager wrote, “The reason I chose to focus only on [the] initial stage of the employment process is because this is the stage likely to be most affected by the barrier of a criminal record.” Pager, The Mark of a Criminal Record, supra note 11, at 948.

[41] See Decker et al., supra note 11, at 111; Pager, The Mark of a Criminal Record, supra note 11, at 953; Pager et al., Field Experiment, supra note 11, at 782.

[42] Positive responses refer to interview invitations or job offers.

[43] Overall Likelihood Ratio χ2 = 14.114, p < .001. No criminal record vs. One-year-old felony Likelihood Ratio χ2 = 12.691, p < .001. One-year-old felony vs. Certificate of Qualification for Employment Likelihood Ratio χ2 = 9.151, p < .01. No criminal record vs. CQE Likelihood Ratio χ2 = 0.339, n.s. “Positive response” refers to interview invitations or job offers. Circles indicate point estimates of percentages. Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

[44] To test the robustness of our results, we also used a model specified with an inverse probability weights estimator and robust standard errors. This model also controlled for job type. The results from this approach confirm the point estimates and confidence intervals presented in Figure 1. The results were as follows. The potential outcome mean (predicted probability of a positive callback response) for the “no criminal record” group was 28.98% (with a confidence interval bound of +/- 8.6%). The potential outcome mean (predicted probability of a positive callback response) for the “one-year-old felony” group was 9.77% (with a confidence interval bound of +/- 5.76%). The potential outcome mean (predicted probability of a positive callback response) for the “one-year-old felony with Certificate of Qualification for Employment” group was 25.64% (with a confidence interval bound of +/- 8.16%).

[45] Recall that one case was excluded because the employer reported that the position had been filled. Because the employer response to this resume, which contained no self-disclosure of a criminal record, could not be determined, we tested how the results presented in Figure 1 may have been impacted had there been a positive or negative response to the resume by analyzing the results of the study (1) assuming that the missing case received a positive response and (2) assuming that the missing case received a negative response. Neither analysis substantively changed the results presented above. Had the employer response to the resume been positive, 29.67% of applicants with a clean background would have received a positive employer response (95% Confidence Interval: 21.02%, 38.24%. Overall Likelihood Ratio χ2 = 14.710, p < .001. No criminal record vs. One-year-old felony Likelihood Ratio χ2 = 13.474, p < .001. No criminal record vs. CQE Likelihood Ratio χ2 = 0.476, n.s.). Had the employer response to the resume been negative, 28.70% of applicants with a clean background would have received a positive employer response (95% Confidence Interval: 20.17%, 37.24%. Overall Likelihood Ratio χ2 = 13.920, p < .001. No criminal record vs. One-year-old felony Likelihood Ratio χ2 = 12.446, p < .001. No criminal record vs. CQE Likelihood Ratio χ2 = 0.292, n.s.).

[46] See statutes cited supra note 16.

[47] See, e.g., Lawrence W. Sherman & Heather Strang, Verdicts or Inventions?: Interpreting Results from Randomized Controlled Experiments in Criminology, 47 Am. Behav. Scientist 575, 578 (2004) (discussing “the crucial role of replication in science”).

[48] See Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2953.25 (West 2016).

[49] See Decker et al., supra note 11, at 115-16; Pager, The Mark of a Criminal Record, supra note 11, at 957-60; Pager et al., Field Experiment, supra note 11, at 784-86; Uggen et al., supra note 11, at 637-39. In fact, studies show that racial minorities may fare worse in obtaining employment than a white applicant even if they do not have a criminal record and the white applicant does. E.g., Pager, The Mark of a Criminal Record, supra note 11, at 958 (“[E]ven whites with criminal records received more favorable treatment (17%) than blacks without criminal records (14%).”).

[50] See, e.g., Douglas N. Evans & Jeremy R. Porter, Criminal History and Landlord Rental Decisions: A New York Quasi-Experimental Study, 11 J. Experimental Criminology 21, 39 (2015).

[51] The impact of gender on the effectiveness of certificates of relief is also an area worth studying. While studies focusing on female ex-offenders have found little impact of a criminal record on employment outcomes, see supra note 11, one should not conclude that certificates of relief are necessarily more beneficial for male ex-offenders. First, there are very few studies examining the impact of a criminal record on employment outcomes for female ex-offenders. While initial findings indicate that female ex-offenders suffer little from criminal record stigma in employment outcomes, replication is needed to ensure that such results are robust. Second, as in the present study, the previous studies focusing on female ex-offenders dealt with the general stigma of a criminal record. Certificates of relief are only partially designed to combat such stigma. They may also provide specific benefits such as removing automatic licensing restrictions, see supra note 18and accompanying text. Therefore, while such certificates may not be as useful to female ex-offenders for reducing stigma for general employment purposes, they could still be effective in removing automatic licensing restrictions or in providing other benefits specified by the relevant statute.

[52] But see Amanda Agan & Sonja Starr, Ban the Box, Criminal Records, and Statistical Discrimination: A Field Experiment 31-35 (Univ. of Mich. Law & Econ. Research Paper Series, Paper No. 16-012, 2016), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2795795 (showing that such “ban-the-box” policies negatively affect minorities, likely because without required disclosure of criminal records, potential employers assume that members of minority groups have criminal histories).